In the intricate world of medical device commercialization, one of the pivotal factors determining market success is the ability to secure reimbursement. Companies invest years and millions of Dollars in designing their product, in obtaining its regulatory clearance/approval, in developing appropriate clinical data and in making decisions regarding its price, but they often do so without considering who would eventually need to decide whether or not to pay for their product.

The entity which will make this decision might be a payer (sickness fund/health insurer), a hospital, a physician group or an accountable/integrated care organization (to name a few examples). When considering its reimbursement/funding decision, each of these entities may assign different values to different product features, a different “intended use” in the regulatory clearance/approval document, different clinical data points, and a different price structure, so working on a medical product without first identifying who your reimbursement decision maker is, is like preparing for the World Steak competition in order to offer a costly steak to a penniless vegetarian, or hiring a vegan chef to recommend a quinoa salad to a dedicated carnivore.

In this focused exploration, we delve into the critical role of identifying the relevant decision maker in order to facilitate the development of the right product, the appropriate wording on the product’s regulatory clearance/approval document, the required clinical data points and the most relevant pricing structure, all designed to meet the needs of the identified reimbursement decision maker.

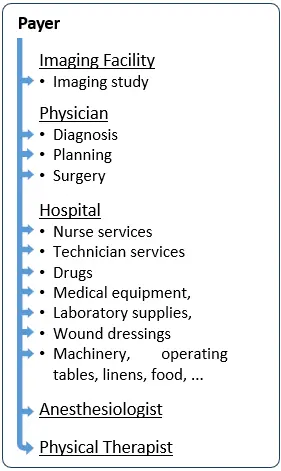

Reimbursement Model 1: Payers as the Medical Device Reimbursement Decision Makers

In the chart on the right, each of the little blue arrows indicates a separate service and a potential separate code, requiring a separate coverage decision by a payer.

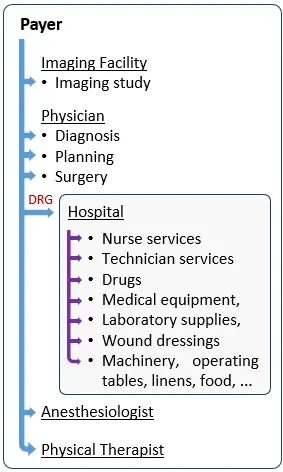

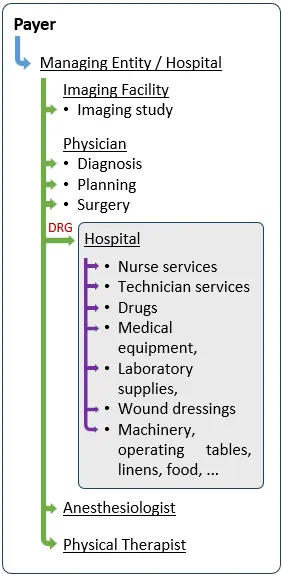

Reimbursement Model 2: Hospitals as Medical Device Reimbursement Decision Makers

This not only shifts the financial risk associated with the treatment of a patient under a specific DRG from the payer to the hospital, but also turns the hospital to your main decision maker, in case your company develops a component that falls under a specific DRG.

As can be seen in the chart on the right, instead of multiple arrows for each discrete component within the hospital, the payer now pays the hospital a single DRG rate and the hospital becomes the decision maker, who decides which devices to purchase, how to use them, and negotiates their prices. In such case, the payer is indifferent to the type, number or price paid by the hospital for your medical device.

Reimbursement Model 3: Accountable and Integrated Care Organizations as Decision Makers

Strategic Implications of Choosing the Wrong Reimbursement Decision Maker

As illustrated above, a physician, a hospital, an Accountable or Integrated Care Organization, or a payer may impose very different requirements before agreeing to reimburse a medical device. These requirements may relate to product features, clinical evidence, regulatory approval language, economic value demonstration, or pricing structure.

Developing a product with the wrong reimbursement decision maker in mind can lead to fundamental strategic misalignment. Companies may invest in features that are irrelevant to the actual decision maker, pursue a regulatory strategy that fails to support coverage requirements, or design clinical studies that do not generate the endpoints required for positive reimbursement decisions.

In practice, these missteps often surface late in development — sometimes after regulatory approval — at which point correcting them may require additional studies, labeling changes, price concessions, or even a complete repositioning of the product. These delays increase development costs, extend time to market, and significantly raise the risk of commercial failure.

Clarifying the reimbursement decision maker early is therefore not a tactical detail, but a foundational strategic decision that directly influences product design, regulatory planning, clinical development, and pricing strategy.

A Structured Approach to Identifying the Right Reimbursement Decision Maker

To identify the correct reimbursement decision maker for a medical device, we recommend starting with a structured medical device reimbursement assessment early in development. This includes mapping money flows and financial incentives associated with the use of the product, identifying applicable reimbursement mechanisms such as codes, coverage policies, and payment systems, and determining which entity ultimately bears the economic risk.

This analysis enables companies to clearly establish whether reimbursement decisions will be driven primarily by payers, hospitals, physicians, or integrated care organizations, and under which circumstances. Importantly, this step should be completed before finalizing product design, regulatory strategy, clinical study protocols, or pricing assumptions.

By validating these elements early and, where possible, engaging directly with decision makers for feedback, companies significantly reduce reimbursement risk and improve their chances of achieving timely market access and sustainable commercial success.

Key Takeaways

- Identify the correct reimbursement decision maker early.

- Align regulatory, clinical, and pricing strategy to their requirements.

- Understand whether payers, hospitals, or integrated care organizations drive coverage.

Frequently Asked Questions About Medical Device Reimbursement Decision Makers

What is a medical device reimbursement decision maker?

A medical device reimbursement decision maker is the entity that ultimately decides whether a medical device will be paid for and under what conditions. Depending on the reimbursement model, this may be a payer, a hospital, a physician group, or an accountable or integrated care organization.

Why is it important to identify the reimbursement decision maker early?

Identifying the reimbursement decision maker early is critical because it directly influences product design, regulatory strategy, clinical evidence requirements, and pricing. Developing a product without clarity on who will decide reimbursement often leads to misaligned clinical studies, delayed coverage, and increased commercialization risk.

Is the payer always the medical device reimbursement decision maker?

No. While payers often make reimbursement decisions under fee-for-service systems, hospitals are frequently the decision makers under DRG-based payment systems. In integrated or bundled care models, the decision maker may be an accountable or integrated care organization rather than the payer.

How does the reimbursement decision maker affect clinical study design?

The reimbursement decision maker determines which clinical endpoints, comparators, and economic outcomes are required for coverage. For example, payers may focus on population-level outcomes and cost-effectiveness, while hospitals may prioritize operational efficiency and budget impact.

Can choosing the wrong decision maker delay market access?

Yes. If clinical or regulatory strategies are designed around the wrong decision maker, additional studies, labeling changes, or economic analyses may be required after regulatory approval. These delays increase development costs and can significantly postpone reimbursement and market adoption.

How can companies determine the correct reimbursement decision maker?

Companies can determine the correct reimbursement decision maker by mapping reimbursement pathways, understanding applicable payment mechanisms, and analyzing who bears the financial risk associated with product use. Engaging early with payers, hospitals, or integrated care organizations can further validate this assessment.